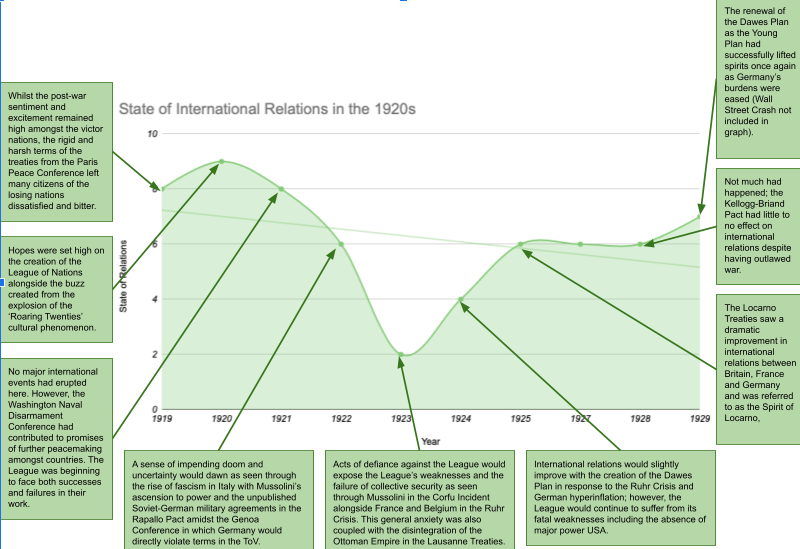

Improved Relations in the 1920s

Improved Relations in the 1920s

Locarno Treaties (1925)

The Locarno Treaties consisted of seven agreements that were negotiated in Locarno, Switzerland between Germany, France, Belgium, Great Britain and Italy in 1925.

The agreements aimed to guarantee peace in Western Europe, secure post-war territorial agreements and improve relations with Germany. These aims could be manifested through:

- Securing borders of the European nations post-WW1

- Guaranteeing Germany’s Western Frontier

- The permanent demilitarisation of the Rhineland

- Negotiations to allow Germany into the League of Nations

One of the most important treaties was the Rhineland Pact which guaranteed British and Italian assistance to act against any violation of the existing borders between Belgium, France and Germany.

The British perspective

One of Austen Chamberlain’s (British prime minister) primary aims entering the conference was to promote mutual friendship and reconciliation between Germany and France who maintained a tense relationship over history. Britain intended for France to dissolve the Cordon Sanitaire (a French system of alliances in Eastern Europe that served to encircle Germany and protect France).

Britain emerged from the conference as a mediator, holding peace in Europe despite its minimal ability to guarantee the security of the Rhine frontier. However, they were in a clear position to be able to dissuade Germany and France from any conflict.

The French and Eastern European perspective

France and their Eastern allies were viewed as the ‘losers’ of the conference. None of the Locarno agreements had committed Germany to respect its eastern borders as Stresemann refused to recognise frontiers he considered to be unjust.

Aristide Briand (French prime minister) entered the conference intending for any pact to respect French ventures with regards to its Polish and Czech allies.

France had lost its ability to enforce the terms of the Treaty of Versailles as it would be transferred to the League of Nations upon Germany’s admission. There was now an additional risk of British and Italian confrontation should France march into Ruhr, Germany as they once did. Briand was viewed by right-wing Parisians as having been duped by Stresemann.

Additionally, Poland and Czechoslovakia received no German guarantee of their territorial gains from the peace treaty. Polish Foreign Minister Alexander Skrzynski was particularly disillusioned as he felt that the security of his country was sacrificed at the conference for the sake of Franco-German reconciliation.

The German perspective

The signing of the Locarno Pact enabled Germany to be perceived as an equal partner in international affairs to its European counterparts. Unlike the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was actively involved in the making of the agreements and its decisions.

Gustav Stresemann (German chancellor) entered the conference with a strategy called Erfüllungspolitik (fulfilment) whereby he would comply and fulfil the terms of the Treaty of Versailles to appease Britain and France. This was a result of his awareness of German’s weak and vulnerable position after the war. He was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in bringing a positive light to Weimar Germany’s foreign affairs. Public confidence in him was also further reaffirmed.

However, extremist parties such as the Nazis were unhappy with the treaties made by the Republic. They viewed it as a betrayal of Germany as the pact confirmed many points made in the Treaty of Versailles. Adolf Hitler would go on to continuously reject the Locarno Treaties through the remilitarisation of the Rhineland in March 1936.

The ‘Spirit of Locarno’

Despite individual dissatisfaction towards the treaties, the conference was largely regarded as a success as it marked a dramatic improvement in relations between Britain, France and Germany.

The ‘Spirit of Locarno’ emerged as a term used to refer to hope for international peace during the interwar period following the agreements made at the Locarno Conference. Expectations were high for further international cooperation and peaceful settlements.

Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928)

The Kellogg-Briand Pact (otherwise known as the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy) was an international agreement aimed at outlawing war. It intended to establish “the renunciation of war as an instrument of national policy”.

It was written by United States Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand. The pact would go on to receive 62 signatories including Germany, France and the United States.

Effectivity or its lack thereof

Despite its theoretical and moral righteousness, the Pact did not live up to its practical aims of enforcing the renouncement of war and militarism. There was an absence of clear and direct evidence as well showing their proposed mechanism to enforce the pact’s terms. Many of its signatories purely began to wage war without a formal declaration, such as the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935.

For Germany however, this pact was significant as it allowed them to be viewed as an equal to the other 61 countries that could be respected and trusted.

Criticisms

The treaty was seen to be extremely idealistic as it contained no sanctions against countries that might breach its provisions and was solely based on the hope that diplomacy and the weight of world opinion would be sufficient to prevent nations from using force. It also did not properly define what constituted ‘self-defence’ and when it could be lawfully claimed.

Dawes Plan (1924)

An economic plan devised by an American banker called Charles G. Darwin between Germany and the Allies of WW1 intended to solve the problem of war reparations established by the Treaty of Versailles against Germany.

Its aims consist of:

- Reducing German reparations in the short term to £50 million per year

- Providing Germany with loans of 800 million gold marks from the USA to assist in its industrial reconstruction

The plan was established following the Ruhr Crisis (1923-1925) and German hyperinflation (1923). Dawes was asked by the Allied Reparations Committee to investigate the problem.

Ruhr was to be fully returned to Germany by French and Belgian troops following acts of passive resistance by the German workers.. The plan would also include staggers for Germany’s reparation payments alongside the restructuring of Weimar’s national bank, the Reichsbank.

Results

Initially a great success, the Dawes Plan ended the Ruhr Crisis. It was able to stabilise the German currency and bring inflation under control. Large loans were raised in the United States and this investment resulted in a fall in unemployment. Germany was also able to meet its obligations under the Treaty of Versailles for the next five years. This economic recovery and improvement in international relations would lead to what was known as the ‘Golden Years’ between 1924 and 1929.

The plan would lead to closer relations between Germany and American investment banks. However, it also led to the French industry being damaged due to its dependency on German coal which was no longer supplied to them after the Ruhr Crisis.

The Dawes Plan would eventually be replaced by the Young Plan as its interim measured and proved unworkable. Its main weakness was that it was short term and relied on Weimar Germany economically rallying. Any economic disaster the USA faced would have direct effects on Germany itself.

Criticisms

Many Germans (primarily conservatives) disapproved of the plan as it did not provide a definite timeframe for repayments and put parts of German industry under international control.

The Young Plan (1929)

An economic revision of the Dawes Plan (1924) formulated by Owen Young and the Committee. Reparations remained a major issue for Germany after the Dawes Plan as they were still in no position to fulfil its financial requirements.

The plan furthered its financial support of Weimar Germany, including:

- Further reducing reparations to 112 billion gold marks to be paid over a definite period of 59 years

- Allowing Germany to be excused from paying two-thirds of its reparations per year if it was to damage its economic development

- Setting up the Bank for International Settlements to handle the transfer of funds

The Committee

The American representatives held more of a dominant position in the committee as reflected by the USA’s wealthy status. The USA saw a strong desire to develop Weimar Germany as an economic entity for the possibility of forming a valuable trading relationship. This plan would also act as a bulwark against communism from the USSR if Germany saw the benefits of capitalism.

The terms of the plan felt too generous for the British representatives. Much of Britain was still bitter from the events and scars of the war, hence political parties did not want to be perceived as being ‘too soft’ on Germany. But upon strong American persuasion, they would eventually accept the plan.

Results

However, the plan was never allowed to be fully implemented as the Wall Street Crash had occurred shortly after its presentation which paralysed the global economy. Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor of Germany in 1933 shortly after also signalised the definite termination of the Young Plan even before its official implementation.

Criticism

Nationalist right-wing politicians in Germany heavily criticised this plan such as Adolf Hitler and Alfred Hugenberg. They believed that accepting the plan’s terms was accepting the Treaty of Versailles. It essentially meant confessing the ‘war guilt clause’ which was not modified in the Young Plan. The President of the Reichsbank, Hjalmar Schact, also disagreed with the plan and resigned from office.